WILLIAM McCAY

3 Investigators Crimebusters Author

An Interview by

Seth T. Smolinske

copyright 2002

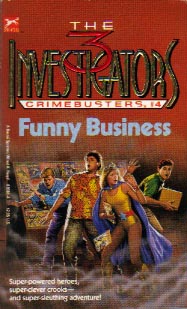

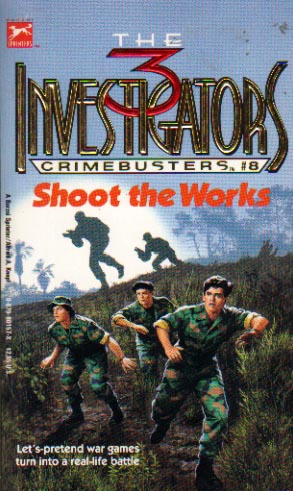

William "Bill" McCay is a lifetime New Yorker and old-time baseball fan: He was born in Brooklyn when the Dodgers still played there, and raised in Queens about a mile and a half from the Mets' Shea Stadium. He lived briefly in Manhattan's Greenwich Village "where baseball apparently wasn't played at all, and high rents drove me back to Queens where I live in beautiful Flushing which is NOT the plumbing capital of the world." Bill wrote two stories in the 3 Investigators Crimebusters series: #4 "Funny Business" published in 1989 and #8 "Shoot the Works" published in 1990.

The following interview took place in the months of June and July 2002, via e-mail. Bill graciously answered (in great length and much humor) all of the questions I asked him, and he urged, "You may want to edit my answers for length - when I get started, it's sometimes hard to stop."

STS (Seth T. Smolinske): What were some of your early literary influences and what led you into your occupation as a writer?

BM (Bill McCay): The reading bug bit me early on, mainly history. I discovered Andre Norton's historical fiction, followed by her sci-fi. Other authors of my youth? Kipling -- the short stories, "Kim", and especially "Puck of Pook's Hill"; Edgar Rice Burroughs, mostly the non-Tarzan stories; mysteries, especially Arthur Conan Doyle, and some of the Alfred Hitchcock anthologies.

I was the first member of my family to graduate college, with a degree in the dubiously useful fields of English and Theater from the Lincoln Center campus of Fordham University. Then came six miserable years trying to make it in public relations and corporate editing. Toward the end of that period I met Pat Fortunato, a free-lancer in children's publishing, who gave me several gigs assisting her on projects. When she went on staff doing a magazine for Children's Television Workshop, she recruited me as her associate editor. Subsequently, Pat went on to found her own book packaging company [Megabooks], and I wrote my first full-length novel creating "book product" as corporate publishing types like to call it. My manuscript helped Pat sell a 12-book series, "Race Against Time". I wound up as head editor for Megabooks.

STS: According to Peter Lerangis [author of Crimebusters #9 Foul Play], you were the editor for some of his writing on the Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew books back in the late 1980's, this must have been at Megabooks, the company that essentially picked up where the Stratemeyer Syndicate left off.

BM: Yes, Megabooks specialized in series for children and young adults. I wrote and edited a lot of books under a variety of pseudonyms and "house names" which allowed series where many different authors contributed to be racked under a single, fictitious author [i.e. - Franklin W. Dixon, Carolyn Keene, Victor Appleton, etc.]. Along the line I was involved with several well-known series: The Bobbsey Twins, Nancy Drew, and the Hardy Boys. Book packagers like Megabooks essentially bear the same relationship to large publishers as independent producers do in Hollywood, developing projects to be distributed by the big boys. Along with the editing job, I was trying to write at least two books a year. I understand the cat is pretty much out of the bag on my participation in another old-time series, Tom Swift. One web site actually lists me as the author on several titles.

STS: Were you familiar with The Three Investigators series before becoming involved with the 3 Investigators Crimebusters?

BM: While I was aware of The Three Investigators when Jenny Fanelli [the 3I editor] approached me, I'd never read any of the books. On the other hand, I'd only read three chapters of the Hardy Boys as a kid. My youthful series reading came out of an old trunk in my great-aunt's barn -- original Tom Swifts, and a horrifyingly badly written series called "The Boy Allies" about a pair of American lads who won World War One. The Robert Arthur books I read to get up to speed on The Three Investigators made me wish I'd discovered them much earlier!

STS: How did you become involved with the 3 Investigators Crimebusters series?

BM: I got a call at the Megabooks office from Jenny Fanelli, who had apparently heard of me from mutual editorial connections. That must have been about 1988, because "Funny Business" came out in 1989 and was the first or second book actually published under my own name. By that time, I had established a reputation for turning out series books quickly and professionally, with an emphasis on mysteries and adventures. The subject of Jenny's phone call was to check my availability for writing a 3 Investigators Crimebusters book. After discussing the offer with my bosses to avoid conflict of interest and getting a green light, I agreed and set to work learning the series.

Let me say, by the way, that Jenny Fanelli is one of the three or four best editors I've encountered in the business. Her editorial letters were wonderful blueprints on how to fix a book. She knew very well when and how to let a writer run free, and when to pull in the reins. For example, she pulled me up when I wanted to name the shifty editor in "Funny Business" Leo Rotwang (after the villain in the movie "Metropolis"). Jenny very rightly pointed out that a teen-aged audience would probably think poor Leo had some sort of venereal disease. So, he became Leo Rotweiler, still a somewhat silly-sounding name, but connected more with a sometimes-dangerous breed of dogs rather than v.d.

STS: It has been said that the Crimebusters series was developed to compete with the relative success of the Hardy Boys Casefiles books from that time. I'm guessing that your experience working with the Hardy Boys books is what may have led Jenny Fanelli to seek you out for the Crimebusters?

BM: As a former editor myself, I'd be very dubious about coming out with a project just to "compete" with something another company was doing. The success of the Hardy Boys Casefiles showed that there was an untapped market among young adult boy readers. Looking at things that way, it only made sense to try a young adult version of The Three Investigators. While there are similarities between the series, there are also important differences.

I don't believe that I was sought out because of my connection with the Hardys -- if anything, it might have been in spite of that connection. Recently, Jenny paid me a very nice compliment, calling me one of the most dependable assignment writers she'd ever worked with. That's what a series editor looks for.

STS: What is your personal assessment/comparison of the two series - Hardy Boys Casefiles vs. 3 Investigators Crimebusters?

BM: I can remember Jenny Fanelli trying to underline the main differences between the Crimebusters and the Hardy Casefiles: "They're more . . . novelistic than what you've been working on," she said.

Since I was younger and feistier back then, I said, "A novel -- that's where you have a protagonist and antagonist, a conflict, rising action that reaches a climax where the hero grows and changes -- and then, because this is a series book, he goes right back to where he was in the first place!"

But the fact is, the Crimebusters books were more novelistic. There's more character development -- the Casefiles were definitely plot-driven. Not surprising, when you consider we were doing twelve Casefiles a year, plus six digest-sized books, versus four Crimebusters coming out at the same time.

Besides the emphasis on plot, the Hardy Casefiles put a premium on action. These books were aimed at the same boy's audience as comic books, Arnold Schwarzenegger movies, and shoot-em-up computer games. When we were laying the groundwork for the new Hardy Boys series, the publisher asked me, "Bill, if you could do anything with the Hardy Boys, what would you change?"

A loaded question. I answered, "I'd blow up that yellow sedan they've been driving since 1930 . . . and I'd have Iola Morton (Joe Hardy's girlfriend) in the back seat when it went up."

For a second, I thought the poor man was going to have a stroke. He sat up very straight, looked at me, then said, "What happens next?" That was our first Casefiles.

Why did I give such an outrageous answer? Well, the yellow sedan gave a completely different cultural message back when the Hardy Boys first came out. That was still the era when Henry Ford could say, "You can have any color you like -- as long as it's black." A red or yellow car meant it was a sporty model. A sedan meant -- wink-wink, nudge-nudge -- it had a back seat. Today, you hear "yellow sedan," especially in New York, and you think "taxicab."

As for blowing up Iola, I wanted to serve notice that no character was safe and that the Hardys should investigate the most serious of crimes -- murder. I'd fought for that when my company, Megabooks, revamped Nancy Drew, and I thought the boys should play for equally serious stakes. We were trying to be as serious as possible -- besides mystery, the Casefiles would draw heavily from the thriller and spy novel genres.

Before this, most teen detectives, like The Three Investigators, dealt only with crimes of property. The Crimebuster, as you know, continued that tradition, remaining deductive mystery stories. Given the comedy element as well, that was probably a wise decision. It's hard to laugh it up in one chapter and find someone dead in the next. Not impossible, but not easy.

STS: Your first contribution to the Crimebusters was 1989's "Funny Business". What's the background on this story?

BM: As an editor who worked on several series, I'd say the one thing I'd look for in a writer was an individual who could quickly pick up what the series was about and run with the concept. A series bible, even a fairly comprehensive one, can only take a writer so far. A lot of the job is reproducing or creating the right tone. For me, one of the more interesting elements was the humor in the 3I books. I wanted to put them in an offbeat setting with the potential for a lot of funny stuff. Since part of my Megabooks job involved looking for new projects and writers, I'd been making contacts in the comic-book scene, especially at comics conventions. A humorous mystery at a con, where things can get pretty wild, seemed a natural for Jupe, Pete, and Bob, so I pitched the idea to Jenny.

I actually saw a review complimenting me for getting the background right. Well, as I said, part of my editorial job involved looking for talent and story material in the comics field. I'd gotten friendly with a young dealer and aspiring artist, Jack Hunter. He was so helpful, introducing me to people and sharing war stories, that I immortalized him as a character in the book.

As I worked my way into the Crimebusters, I noticed that the other authors seemed to have it in for poor Jupiter Jones. It seems they were punishing Jupe for his overbearing personality in the previous stories. Maybe it's because Jupe and I share the same sort of physique, but I felt a certain sympathy for him A lot of bright, self-confident kids get thrown for a loop by puberty and the world of teendom. So, what better subplot for my first 3I book than to have Jupe fall in love?

STS: I know of several people who list 1990's "Shoot the Works" as one of their favorite Crimebusters stories . . .

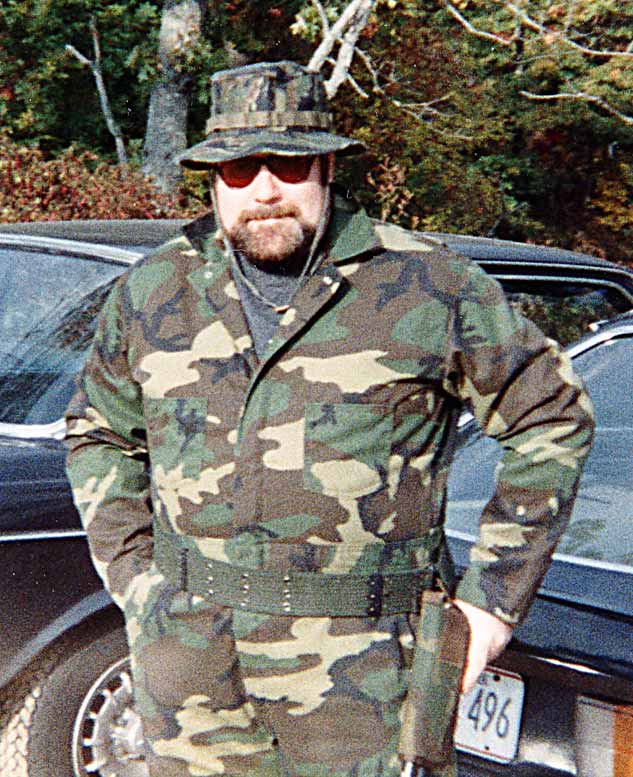

BM: "Shoot the Works" came out of research I was doing into the phenomenon of paintball. The game is sort of high-tech "Capture the Flag" with people shooting globules of paint from CO2 guns instead of tagging one another. My research got pretty heavy-duty -- I actually spent a day playing the game and touring a paintball facility.

I "killed" one poor guy who was so shocked, I had to shoot him again -- an incident that found its way into the book. Along the way, I got "shot" twice myself but never felt the full agony of defeat. The 200-mph paintballs caught me in the holster and in the steel-reinforced toe of my boot.

STS: "Shoot the Works" was one of the very few U.S. 3I stories that wasn't issued by the German publisher. Speculation has been made that perhaps the publisher felt it was too violent. Any ideas?

BM: I hadn't realized that the book never made it into the German market, although maybe I should have deduced it -- the only German-language 3I book I received was "Die drei ??? und die Comic-Diebe" ("The Three Investigators and the Comic Thief", their translation of "Funny Business"). I don't know that "Shoot the Works" was all that violent, but the perception might have been a drawback. There was a distinct decision to keep guns off the cover of the American edition. Perhaps that was a consideration for the German publishers. Then, too, the paramilitary aspect of paintball teams might have been a problem. On this side of the Atlantic, I've heard people attack paintball players as gun nuts, militarists, and proto fascists. All I can say was that most of the paintball people I met were playing a game -- and for the more professionally involved folks, one of the biggest concerns was safety.

STS: Did you write any Crimebusters stories that weren't published?

BM: I may have thrown around a couple of ideas, but I certainly wasn't working on anything when the Crimebusters series was canceled.

STS: I may be charting forbidden territory here, but I'm incredibly interested in learning more about how juvenile series book authors are paid for their work. It's understood that receiving a "flat fee" or lump sum payment for their contribution was/is the standard practice of payment for juvenile series book authors. The Three Investigators have been an exception from the beginning with authors earning a percentage based on the sales of their work. In general, has that "flat fee" practice changed in the last 20 years? As for royalties, do individual authors negotiate their percentage?

BM: My experience was that most series writing was "work for hire" -- a non-royalty situation. For long-running series, especially media tie-ins, the money pie was already cut up into so many pieces, there was nothing left for an individual author. I did have some profit participation in "Race Against Time," but my first royalty book was "Funny Business". I just dug through some old royalty statements -- the authors received ten percent. Over the years, I just about doubled the up-front money I got from the book.

I can't speak for the other authors, but those were the days before I had an agent. So whatever negotiating there was, I did for myself -- not that I recall any big bargaining sessions. These were pretty much standard contracts. I don't think there was much room to maneuver on royalty percentages. The pay was decent, there was a royalty, I'd be working on a well-known, respected series -- what was there to fight over? I've taken on a lot of projects since then, for worse pay and more headaches. To do a good, funny book for a good buck, working with a very good editor -- to me, that was not a bad deal.

STS: What have you been up to since Crimebusters?

BM: When the 3I were retired again, Jenny approached me to help launch the "Young Indiana Jones" series, and I wound up doing eight books. Somewhere in there, I finally left Megabooks to try my luck as a full-time free-lance writer. I started doing some work for grown-ups. Eloise Flood, a colleague from Megabooks, and I wrote a Star Trek: The Next Generation book, "Chains of Command". We actually enjoyed several weeks on the NY Times Paperback Bestseller List. My comic book connections from "Funny Business" developed into "Riftworld", a series of novels done with Stan Lee. Then came a five-book series carrying on what happened after the film "Stargate" (not to be confused at all with the TV series "SG-1").

There were also a number of young adult novels -- some forgettable, like a horror trilogy which will remain nameless. Memorable but not successful was another try at YA mystery, "Scene of the Crime". The intent was to subvert all the "rules" for teen books of the time. We had a first-person male narrator, a humorous take on romance, and a plan for the characters to grow, change -- and AGE! The first four books were to take place in junior year of high school, the next four in senior year, the characters would be college freshmen in the next set, etc. Ah, well. The plug was pulled after the first four, I wrote two under the house name "Mickey Alman."

More recently, I got involved in the Tom Clancy Net Force phenomenon, doing six books in the YA series. One, "Cold Case", allowed a deep homage to some of the classic detectives, not to mention a fun Rex Stout/Nero Wolfe pastiche.

Lately I've been doing some fantasy short stories. I've got some feline fantasies in "A Constellation of Cats", "Familiars", and "Pharaoh Fantastic", not to mention a funny fantasy story upcoming in an anthology entitled "Vengeance Fantastic". I'm also working on some proposals for a Renaissance fantasy novel (sword fights!) and a military science fiction trilogy. And here's some hot news! It's just been announced that I'll be doing a fantasy novel based on the Mage Knight game series, due out next year.

Having just redone my bibliography, I can officially state that I've done 76 different titles, from picture books to a hard-edged cops and Mafia ghostwriting job. The Three Investigators, however, remain one of my sentimental favorites.

3 Investigators Crimebusters author William "Bill" McCay conducting research for #8 "Shoot the Works" circa 1990:

Return to Three Investigators Authors/Artists page.